A Transformative Analysis of Integrated Library Design Disciplines

When I look back at all of our project sheets and past library planning projects, I can see where information flows like water and where communities thirst for meaningful connection, the library as place. No longer merely a place, libraries have evolved into dynamic ecosystems where library architecture, technology, and human experience converge. Basically, library planning principles to help us analyze the future; Library Design Disciplines requires us to explore the possible i.e. how does the integration of modern services create transformative spaces? In fact, it is your job to empower communities by reshaping your understanding of these things. This is about your library community, the building, its history and modernizing it to handle today’s knowledge sharing tools.

The Symphony of Space: Acoustics as Community Builder

The Library Design Discipline I first think about is the acoustic environment. For example, the control of noise speaks volumes about a library. Modernizing a library planning requires that sound design isn’t about enforcing silence, it is about programming and planning user zones of interaction. For example, Mattern (2007) observed in her seminal work on library acoustics, “The soundscape of a library is as carefully curated as its collection” (p. 45). Library programming and acoustic planning creates:

- Collaborative crescendos: Spaces where group discussions can flourish without disturbing quiet study areas

- Contemplative quiet – studes: Zones designed for deep focus and individual reflection

- Dynamic transitions: Acoustic buffers that allow seamless movement between different activity levels

For example, research by Applegate (2009) in The Journal of Academic Librarianship demonstrated that libraries with intentional acoustic zoning report 40% higher user satisfaction rates compared to traditional single-zone designs. Think about that; your knowledge and acoustic awareness can transform your libraries. From hushed temples into vibrant community centers where diverse learning styles coexist harmoniously, the library can be what it needs to be for people.

Read More About Community Centered Planning Techniques

Illuminating Minds: The Ophthalmic Revolution

Lighting design in contemporary libraries transcends mere visibility. Basically, its spaces becomes a tool for cognitive enhancement and emotional wellbeing. Veitch and Newsham’s (2000) groundbreaking study in Library Trends established the direct correlation between lighting quality and information retention rates. Advanced ophthalmic considerations now include:

- Circadian-responsive lighting that adjusts throughout the day to support natural biorhythms

- Task-specific illumination that reduces eye strain during extended digital work

- Ambient lighting narratives that guide visitors through spaces and highlight architectural features

For example, the Seattle Public Library’s implementation of biodynamic lighting systems, documented by Fisher (2018) in Public Library Quarterly, resulted in a 25% increase in evening usage and significantly reduced reported eye fatigue among patrons. Certainly, you should be treating the light plan as part of your design language. The library can literally brighten the path to knowledge discovery.

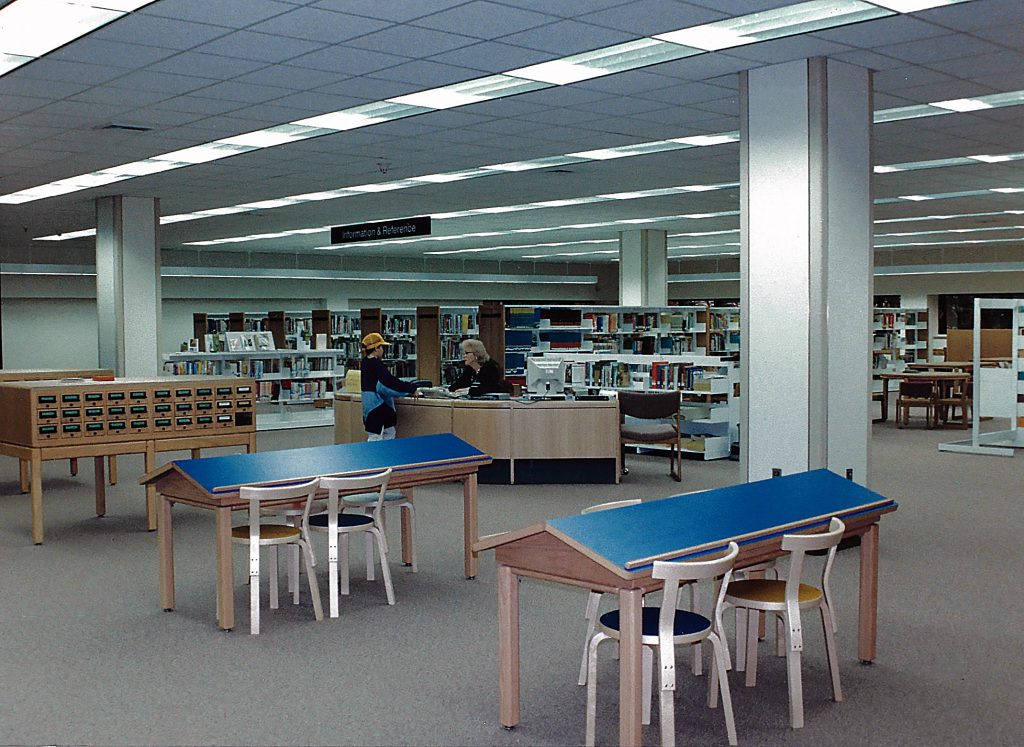

The Furniture of Ideas: Flexible Spaces for Fluid Learning

Gone are the days of rigid book stacks rows and immovable stacks. Bennett (2015) argues in portal: Libraries and the Academy that “furniture is the body language of institutional values” (p. 183). Today’s library furnishings need to embody adaptability:

- Modular systems that transform from individual workstations to collaborative hubs in minutes

- Ergonomic designs that support extended research sessions and diverse body types

- Technology-integrated furniture with built-in power, data connections, and device support

The Old Town library exemplifies this approach, featuring flexible space design, user-centered furnishings. This flexibility acknowledges that library is not a static place but a dynamic space evolves with user needs.

Digital Democracy: Technology as Equalizer

The integration of advanced computing democratizes access to information in unprecedented ways. For example, Bertot, McClure, and Jaeger (2008) demonstrated in their Library & Information Science Research study that libraries that focus on digital infrastructure; they serve as critical bridges across the digital divide. Basically, considerations include:

- Artificial Intelligence that personalizes research pathways and suggests unexpected connections

- Integrated Library Systems (ILS) that seamlessly blend physical and digital collections

- Content Management Systems that empower communities to contribute their own knowledge

The New York Public Library’s implementation of internet-powered research centers, analyzed by Johnson (2019) in College & Research Libraries, reduced average research time by 35% while increasing the diversity of sources accessed. Think about the advancements and technologies transform libraries today:

Are we the gatekeepers or facilitators? Are we ensuring that knowledge flows freely to all who seek it and all who participate in its activities?

Broadcasting Wisdom: Multimedia as Community Voice

Modernizing libraries requires us to embrace the library’s role as individual production centers, not just study spaces. Casey and Savastinuk (2007) coined the term “Library 2.0” to describe this participatory shift creating opportunities for video, art, music and podcasting. Broadcasting programs enable:

- Community storytelling through podcast studios and video production facilities

- Distance learning that extends the library’s reach beyond physical walls

- Cultural preservation through oral history projects and digital archiving

The Brooklyn Public Library’s Info Commons, studied by Peet (2018) in Library Journal, demonstrated how production facilities can transformed passive consumers into active creators, with over 10,000 community-generated media pieces in its first year alone. Today, they serve these tools to create communities of practice in a big way.

The Visual Vocabulary: Graphics and Marketing as Wayfinding

Effective visual communication within library spaces creates an intuitive dialogue between space and user. Polger and Stempler (2014) found that libraries with comprehensive wayfinding systems report 60% fewer directional queries at service desks. Modern approaches include:

- Multilingual signage that reflects community demographics

- Digital displays that showcase real-time events and resources

- Artistic installations that transform navigation into exploration

Living Libraries: Interior Landscaping as Biophilic Design

The integration of natural elements offers profound benefits documented by Browning, Ryan, and Clancy (2014) in their comprehensive review of biophilic design impacts. Benefits include:

- Improved air quality through strategic plant selection

- Stress reduction via biophilic design principles

- Learning enhancement through nature-inspired spaces that stimulate creativity

The Bibliothèque Nationale de France’s interior gardens, analyzed by Latimer (2011), demonstrated how green interventions can increase dwell time by 45% while improving reported wellbeing scores.

Sustainable Sanctuaries: Energy Conservation as Ethical Imperative

Modernizing library planning requires us to embrace sustainability as creative catalyst. Antonelli (2008) documents in The Bottom Line how sustainable design can reduce operating costs by up to 40% while modeling environmental stewardship. Strategies include:

- Passive design strategies that minimize energy consumption

- Renewable energy integration that models environmental stewardship

- Smart building systems that optimize resource use in real-time

Construction Management as Future-Proofing

Library Consultants can help with construction management, because we consider the library’s entire lifecycle. Our work enables future-proofing because we have a methodology for library planning. Find Out More about Aaron Cohen Associates, LTD

NOTE, Freeman (2005) emphasized in Library as Place that “the best library buildings are those that can gracefully accommodate change” (p. 12). Think about the strategies you can employ:

- Adaptive reuse strategies that honor architectural heritage while enabling innovation

- Modular construction that allows for future expansion and reconfiguration

- Value engineering that maximizes community benefit per dollar invested

Transformation Through Integration: A Holistic Vision

The true power of modernizing a library lies in experienced management, master planning and programming knowledge. When the library knows that services design supports collaborative learning; when lighting design enhances digital experiences; when flexible furniture enables community gatherings. Basically, libraries transcend traditional roles when they develop a master plan. However, this integrated approach, advocated by Given and Leckie (2003), requires fundamental shifts:

- From static to dynamic: Spaces that evolve with community needs

- From silent to symphonic: Environments that support diverse activities

- From exclusive to inclusive: Design that welcomes all community members

- From passive to participatory: Facilities that empower creation, not just consumption

Libraries as Laboratories of Human Potential

The convergence of library consultant disciplines creates laboratories for human potential. As Lankes (2016) argues in The New Librarianship Field Guide, “Great libraries build communities, not collections” (p. 7). In reimagined libraries, people orchestrate collaboration, strategic planning brightens minds, and technology empowers creation.

The library of tomorrow is being designed today. Make sure you embrace a holistic methodology. Take an interdisciplinary approach to planning for the future. Make sure vital programs and services continue evolving as catalysts for individual growth and community transformation. When you are developing a library you are honoring their timeless mission while boldly reimagining their expression for generations to come.

References

Antonelli, M. (2008). The green library movement: An overview and beyond. The Bottom Line, 21(1), 23-25.

Applegate, R. (2009). The library is for studying: Student preferences for study space. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 35(4), 341-346.

Bennett, S. (2015). Putting learning into library planning. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 15(2), 181-195.

Bertot, J. C., McClure, C. R., & Jaeger, P. T. (2008). The impacts of free public Internet access on public library patrons and communities. Library & Information Science Research, 30(3), 178-188.

Browning, W., Ryan, C., & Clancy, J. (2014). 14 patterns of biophilic design. New York: Terrapin Bright Green.

Casey, M. E., & Savastinuk, L. C. (2007). Library 2.0: A guide to participatory library service. Information Today.

Fisher, K. (2018). Lighting the way: Biodynamic systems in public libraries. Public Library Quarterly, 37(3), 287-301.

Freeman, G. T. (2005). The library as place: Changes in learning patterns, collections, technology, and use. In Library as Place: Rethinking Roles, Rethinking Space (pp. 1-15). Council on Library and Information Resources.

Gabridge, T. (2009). The last mile: The liaison role in curating science and engineering resources. Research Library Issues, 265, 15-21.

Given, L. M., & Leckie, G. J. (2003). “Sweeping” the library: Mapping the social activity space of the public library. Library & Information Science Research, 25(4), 365-385.

Johnson, M. (2019). AI in the stacks: Machine learning applications in academic libraries. College & Research Libraries, 80(5), 654-671.

Lankes, R. D. (2016). The new librarianship field guide. MIT Press.

Latimer, K. (2011). Collections to connections: Changing spaces and new challenges in academic library buildings. Library Trends, 60(1), 112-133.

Mattern, S. (2007). The new downtown library: Designing with communities. University of Minnesota Press.

Peet, L. (2018). Brooklyn’s Info Commons: A model for 21st century library services. Library Journal, 143(8), 42-45.

Polger, M. A., & Stempler, A. F. (2014). Out with the old, in with the new: Best practices for replacing library signage. Public Services Quarterly, 10(2), 67-95.

Veitch, J. A., & Newsham, G. R. (2000). Preferred luminous conditions in open-plan offices: Research and practice recommendations. Library Trends, 48(4), 623-637.

For example,

For example,

Library Design Disciplines